Love Run Gold

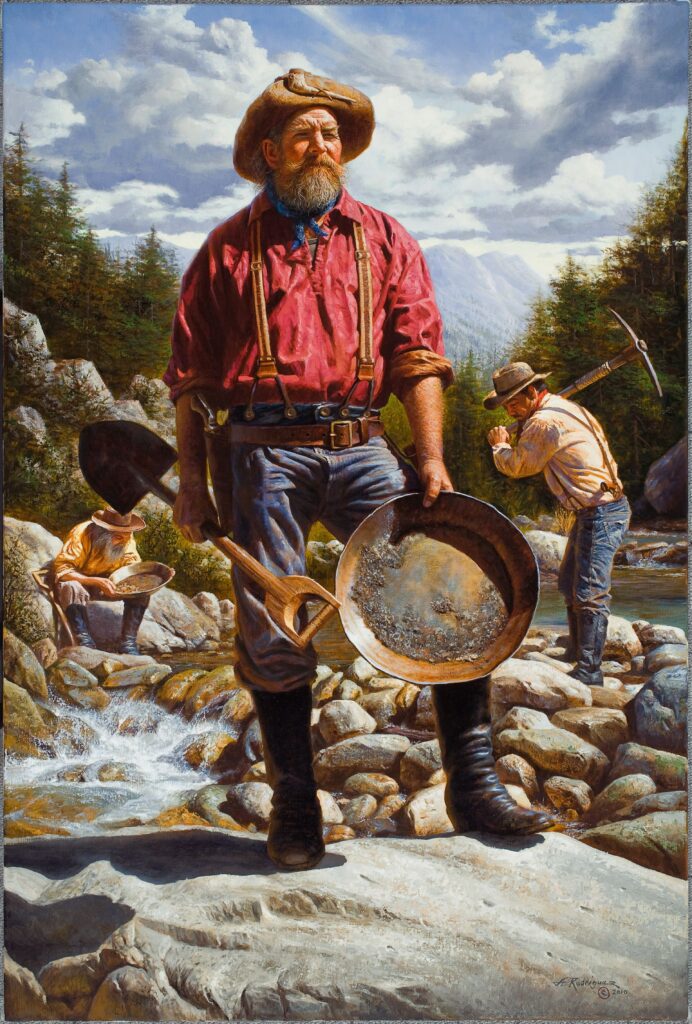

Gold Rush (1954) by Alfredo Rodriguez

Samuel kept no mirrors in his home, and it wasn’t that he couldn’t afford them, though that was true enough. In fact, since his wife’s passing, he hadn’t worked even one earnest day’s labor. Every morning started the same. He would wake up, pray that the day would be his last, rub his wrinkled eyes, start a fire, and head into the wilderness while his cabin warmed. By the time he checked all his traps and foraged enough grub for breakfast, the golden hue of the Oregon sun had usually brought his small abode to life. But he never stayed inside for long. After filling his stomach, he would make for the mountains where the gold still slept under sheets of quartz and sandstone.

It was more the idea of gold than the real thing that kept him in the trade. Before that, it was to provide for or to impress Agnes. He was never sure which. Either way, that well of motivation had run dry. Some days, he wouldn’t even bring his pickaxe or panning kit. He would simply stroll through the forest, avoiding where he could the youthful men with the luster of goldlust in their eyes.

On this particular morning, he did take his instruments, more for show than anything. The traps he set last night all came up empty, so with a cramping gut, he put metal to stone. The place was picked at random, but it mattered not. The rocks shattered and the sweat poured all the same, and that was all he was after anyway—to exhaust the grief, to make every muscle ache. Anything to make the sleep come quick at night, for that’s when the thoughts of her haunted him most.

Blow after blow, the wood’s vibration numbed his hands splendidly. Shrapnel stung his legs such that he knew there would be blood to clean later. Yet somehow, through the haze of hard, repetitive work, an image of Agnes leapt into his mind, unexpected and unwanted. Fighting back, he raised his tool to the sky and made a slash at the woman who left him, who hurt him. When it collided with the mountain, the tip of the blade shot into the forest with the ringing of steel.

He examined the tool’s injury and grunted at the old fool who made it. If Agnes had been there, she would have laughed. But Samuel didn’t share her light spirit. He knew this meant a trip to town, and he loathed the thought. Packing his things, he returned early to the cabin. There, he unearthed his last nugget of gold, wrapped in Agnes’ handkerchief, and took off for the general store, two miles West.

The store cashier greeted him warmly, “How do you do, good sir?”

He passed the counter without even a glance. Finding a decent enough pickaxe, he dropped it on the counter with his gold.

“I’m terribly sorry, but we no longer accept gold in the raw,” said the man behind the counter.

“Since when?”

“Since Betty, bless her heart, accepted a piece of fool’s gold a fortnight ago. You’ll have to make a trip to the bank. I reckon you’ll fetch a half dozen Spanish dollars for that prize you got there.”

“Where?”

The man leaned across the counter to point the way, “Well just down the road yonder. Fifth building to the right. Bright blue sign. You can’t miss it.”

Samuel placed the gold in his pocket and walked out, leaving the swigning doors to wave his adieu.

The bank was bustling with a variety of odd characters, each adding their own bothersome voice to the midday clamor. At last, he made his way to the front where a young woman with wide eyes and rosy cheeks smiled at him.

“Welcome to Washer Creek Trust Company. How may I service you, sir?”

Again, he let the lump fall on the rugged wood booth. “Silver dollars,” he demanded.

“Certainly!” she chirped. Taking out a small scale with which to weigh the gold, she did the calculus and returned him seven shining coins. “Will that be all—Sorry, I didn’t catch your name.”

“Samuel.”

The word evoked an affectionate smile, which she quickly tried to hide behind a cough.

“What?”

“Oh, nothing,” she said, shaking her head. “It’s just that that was my grandad’s name. Samuel Hershaw.”

Though he thought he recognized the name, he decided not to mention it. But simply staring at her gentle features proved too much for him, so he offered, “Is that so?”

“Yes, sir! He was a fine gentleman. Even gave me my first golden nugget, he did.” Then, remembering herself, she said, “Excuse me. Ma’ma says I ramble. Will that be all, Samuel?”

Just then he thought that this girl might be the first pure creature he had happened upon since starting out West. He wanted for her to continue, for her to let trickle that melodious voice until the sun went down. Instead, he simply replied, “That’ll be all.”

Even before he could turn all way round, she stopped him. “Aren’t you going to ask me mine?” she said, loud enough to turn a few heads.

“Your what?” he asked, pleasantly surprised to have her attention again, even if it came at the cost of the others’.

“My name! It’s Lucile Hershaw.”

This was even more of a surprise. To retain her maiden name in a town saturated with hungry young men, some more rich from gold than was good for them, meant she was a deeply backward girl or otherwise the most resilient little thing he had ever laid his eyes on.

“Okay, Lucile. Good day.” With the tip of his hat, he was done.

Back at the cabin, Samuel didn’t think about Agnes for the first night since her passing. All thoughts of her had been chased away by that peculiar girl Lucile. Or perhaps not chased away but swallowed up.

On waking, however, the dull pang of despair weighed just as heavy on his heart, made the worse by guilt for his thoughts of Lucile. Continuing his morning ritual, he went out to work with his new pickaxe in hand. If it were possible, Samuel was even less effectual than usual, and it wasn’t just that his new pickaxe was cheaply made and unfamiliar to him, though it was that too. He felt distracted. A cool disregard had washed what little ambition remained. He didn’t know its name, but that didn’t change what it was: Samuel was lonesome.

It went on like this for some time. Many days, in fact. What eventually broke the spell was the sight of a young couple enjoying a picnic not far from his cabin. He spied behind a barberry bush as they giggled and blushed and did all the things that young people who are in love do. He saw himself there, sitting beside Lucile in a floral dress. He imagined the grass tickling her delicate feet and the wind blowing her blond hair. It made him jealous of the two, terribly so. When they took to kissing one another, he sprang from behind the bush and began shouting at them.

“Get off my property! Shoo! Get!”

The happy couple ran away from the middle-aged man, his red face made all the more so by the unkempt, graying beard it hid behind.

Standing there, trying to catch his breath, he cursed himself, cursed Agnes, and even almost cursed Lucile before he caught himself. She was the only light in his life. If he were to snuff out that candle, the darkness would surely drown him.

Knowing this, he trained his thoughts on her. It was not an easy flame to fan. It had been months, and he could hardly remember her face. What he needed, he told himself, was an excuse to go back to town. Better still, the bank where she worked.

So, the next morning, he carried his implements off to the mountain without rubbing his eyes or starting a fire or scratching around for food. His axe worked furiously against the ground, chipping away slabs the likes of which a man half his age could be proud of. But nothing came of it. He redoubled his efforts the next day. And the day after. And the day after that. Until another week had passed.

By now, his irascible loneliness was unwieldy; it shot out of him at unexpected times and at unexpected victims. Once, he passed a tall, wiry man with a burlap sack and a shovel. He was whistling the tune of “Sweet Betsy from Pike”.

Surely this man has struck gold and is on his way to town. What if he goes to the bank? Her bank. What if she strikes a conversation with him as she did me?

The thought drove him wild. He made some excuse to bark obscenities at the man before continuing on with his work.

Another day, he crossed paths with a fellow gold rusher who had just blown into the area. He asked Samuel where the choice spots for panning were. Samuel eyed his broad shoulders and clean, chiseled chin. He wanted to show him to the river if only to put it in the casanova’s lungs. If Lucile ever caught sight of this young buck, they would be wed before month’s end, he was sure of it.

“You can do your panning in the lake of burning sulfur, if you like,” he answered.

“What’s the matter, old man? We’re all out here for the same thing, aren’t we? Can’t you help a brother out?”

“I’ll help you to the back of my hand if you don’t keep walking.”

“You have an awfully large mouth for an old man,” the man replied.

“I wish your ears were the same size as my big mouth. Didn’t you hear? Keep walking, blunderbuss.”

“Have it your way.”

The man sucker punched old Samuel with a left hook that connected perfectly with his left temple. He hit the floor with a thud. When he woke, it was nightfall. The man had stolen his panning kit but was gentleman enough to leave him his pickaxe. With it, he worked all through the night more ferociously than ever, determined to return to the bank when it opened.

At last, in a little burrow on the side of a hill, Samuel found an ounce of gold under only three inches of rock. He yelped and jumped for joy, not because he found gold but because he now held a one-way ticket to town. Quickly covering the spot with leaves and pine needles, he ran back home where he washed up and donned new clothes with his best suspenders.

There was just enough time for him to make it to the bank and back before the crowd. On his way, he kept his eyes fixed to the ground. A stump here, a root there, this rock, that stick; there were as many distractions as there were ways to say what he wanted to her. Never a man for words, he rehearsed them all.

Soft voices slowly drifted in, filling the once empty spaces between the songs and scuttles of the wood. He knew town was close now. He said two prayers. The first to God for luck. The second to Agnes for forgiveness for the first.

His boots hadn’t long been on the dusty red street before an unwelcome thought occurred to him. What if I am no longer handsome? What if my months of mourning have turned me into a spectacle? Presently, it seemed that everyone passing was staring, pointing fingers behind his back, perhaps whispering cloy pities over him. He needed to know before going to the bank. He saw a mirror outside the barber shop but hesitated. To him, mirrors were not an option.

He grabbed the attention of an old woman standing near. Skipping the pleasantries, he asked her, “Miss. How do I look?”

She looked him from head to foot. He was all aflush. The gold nugget bounded nervously in his right hand, and he wore the look of a man on his way to the gallows. Sweetly, she said, “Like a man in love.”

At last, he arrived in the lobby of Washer Creek Trust Company. He felt his entrails constrict his stomach. His eyes scanned the busy room for Lucile’s face. Not finding it, he placed himself in line behind a counter where a fat woman sat on her stool, chewing a stick of jerky.

“Next,” she droned.

“Is Lucile in?”

She looked at him through half closed eyes. “Would you like to make a transaction?”

“I’d like to see Lucile. Please,” he added with effort.

“This is a bank, sir. Do I look like Lucile’s mother?”

He had a feeling that she had seen this show before. His cheeks were growing hot.“I just want to know if she is working today. Can you at least tell me that? Have the gold, if you like.” He tossed the one ounce nugget on the stall desk.

The woman looked flatly at the metal. “She no longer works here, if you must know.” She snatched the gold faster than her dimpled hand should have been able to. “Will that be all?”

Feeling slightly nauseous, he swung around and left the bank. Outside, he kicked the dust and punched his thigh. How could he be so stupid? He had waited too long, and she left town. In this new world with its endless frontier, she was surely lost forever.

He sat at the foot of the bank stairs for a long time and watched the people walk by as if the world was no different than it had been that morning. He stared at the horse tied up in front of him. How he envied dumb beast. Life was simple for their kind. No love. If you wanted sex, you just did it. And if you were old and wanted to die, you went off into the wilderness and just did that too.

Half-conscious of a stinging in his eyes, he raised his hand to shield him from the sun that had just sunk below the veranda. Had it really been a full day? It struck him that he must be going if he were to make it back by dusk. Dusting himself off, he forced one leg in front of the other again and again until he was back in the woods. There, the silence and the trees restored him somewhat. It was a mindless endeavor anyway, he told himself. Love was a young man’s game. A million things would have had to go right for him to ever catch a date with her. It was better this way. Life alone was cold but easy. Predictable. A fitting way for a man like himself to make his leave of the world.

Still, the sound of her voice hung in his ears. He could hear it still, as though it were singing a sad song to the trees. A ways further, and the song grew louder. He looked around, half expecting a woodland fairy to dance in front of him. But, sure as day, it was the voice of Lucile. The song was one he remembered from church.

As I went down in the river to pray

Studying about that good old way

And who shall wear the robe and crown

Good Lord, show me the way!

O brothers let’s go down

Let’s go down, come on down

Come on brothers let’s go down

Down in the river to pray

Samuel followed the voice to a riverbed not a quarter mile off his trail. Coming upon the place, he saw through dense, green leaves the form of a woman bathing. A ember of joy lit in his chest as he caught sight of the face. It was Lucile indeed, as stunning as an angel illumined by the golden rays of sunset. Quickly, he turned his back. If all the world went up in flame like Sodom, still her purity must be protected.

What was she doing bathing in the forest so far from town, he wondered. Whatever the reason, he decided it his duty to see that she arrived safely back from wherever she came, but to do so at a distance, lest he scare or scandalize her. So, as the sun fell further, he sat there amongst the brush, straining his ears. At last, the sound of disturbed water ceased. Then came the silence of drying off and getting dressed. Only at the snapping of twigs and the crunch of leaves did he finally make brave to turn around. Indeed, she was walking now, but right in his direction. He froze. Hunter’s intuition told him to flatten himself, but he couldn’t make himself do it. He wanted to be found. He wanted to be seen.

But he had no idea how shrewd were her hunter eyes.

“Are you going to stay hidden there all night, Samuel?”

He tried to swallow, but his throat was dry as sand. “No, ma’am,” he croaked. “I wasn’t watching,” he added eagerly.

“I know you weren’t. Most would, but not you.” She was face to face with him now, a gentle smile across her lips. She was wearing a cherry red dress with robin blue flowers breezing from one side to the other.

Unconsciously, he bowed to escape her eyes. “I’m terribly sorry; I heard your song. I only meant to see you safely home.”

“But I am home. My tent is just over yonder.”

“You sleep here, in the woods?”

“Tonight I do.”

“Why?”

“It’s the same reason I do in every place at some point or other. It’s the men. They chase me across town as if I were the only woman they’ve ever seen. It’s never long before they find where I stay. Then it’s even less long before one or other tries to make their way in at night. I recon tomorrow I’ll be off to wherever the Lord leads me.”

Samuel thought long and hard. “You can stay in my cabin tonight.” He looked her in the eyes. “I’ll sleep outside. You have my word, Lucile.”

She hesitated for a moment, looking him up and down. Then she smiled. “Okay, Samuel. Just for the night. Thank you kindly,” she said with a curtsy.

He gathered her things for her quickly enough to mind sundown but slow enough to not impart the eagerness of the young men from whom she’d been running. They were back on the trail in a short while, though that was the part Samuel feared most. As he led the way a few braces before her, he tried to remember the things he had rehearsed on that same trail just that morning. Feeling her eyes were on the back of his head, he couldn’t think properly at all. So, he remained silent with his jaw clenched. This, it so happened, was the best thing he could have done for the woman who had for so long endured young men running their mouths at her. She drank in his strong silence like the forest floor after a long awaited rain.

Back at the cabin, he rekindled the fire and showed her about the place, apologizing for the mess as he went.

“It’s not much, but you’re welcome to anything you like,” he said, brushing crumbs off the table.

“It’s just fine.”

He nodded. “I’ll get some supper on the stove. If there’s anything you need, just let me know.”

“I think just the bathroom for now. I’d like to brush my hair if that’s alright,” she said.

“Of course. Right over here.”

“Thank you.” She shut the door behind her.

He took a deep breath and tried to collect himself. It did nothing for the palpable tension that had followed them into the cabin. She was the first woman, the first anyone, to step foot in his cabin since his wife’s passing. He was sure he had lost all manners in that time, and this was hardly the time to practice.

Moving to the kitchen, he started on a skillet with what little food he had stored. He burned it, of course, but she said nothing as they sat down on opposite ends of his table. He had just lifted his fork when her soft voice shattered the silence.

“Shall we say grace?”

“Of course.” He put it back down, waiting for her to continue.

But she only bowed her head and pressed her hands together, waiting for him to take the lead. He cleared his throat, trying to unbury what little religious education his mother gave him as a boy.

“Ahem. Dear Father, bless us, O God, and these your presents, which we’re going to receive from your bounty, through God… Amen.” He crossed himself and watched to see if he had gotten it right.

She crossed herself too and picked up her fork. If he got the words wrong, she didn’t show it.

“I hope my hair is not a proper mess,” she said. “I’m afraid I’m helpless without a mirror.”

He swallowed his bite unchewed to jump at the remark, “You look lovely.”

He didn’t notice her cheeks glow a deeper pink. “Thank you.”

“Where are you from?” he asked.

“I was born in Montana. That’s where my Grandad settled back in 1827.”

“Samuel Hawthorn,” he remembered.

“That’s right.”

“Why is that name familiar to me?”

She dropped her head, paying closer attention to the dish. “He was a known name around those parts.”

“Why’s that?”

She stopped eating. “Well, for his goodly fortune, I suppose.”

Then Samuel recalled how he knew the Hawthorn name. “That’s right. He was the first man to strike gold in the Americas, wasn’t he? Goodly fortune—why, he hit a mine I recon none’ll ever. That’s your grandad?”

“That’s right.”

“Why, with gold like that, I’da thought you’d be on the shore of some palace off the Mississippi enjoying a plate of lobster right about now.”

She said nothing.

Forgetting himself, he asked, “What’s a girl like you doing in a dog town like Tualatin?”

Samuel saw a tear drop from under the golden waterfall of her bowed head. Again, he felt nauseous.

“I… I’m sorry,” he whispered. “I only meant to…” But he didn’t know where that sentence ended.

“It’s alright.” She lifted up her head and brushed away the dew in her eyes. “It’s a fair question.”

He allowed her to continue.

“I ran away from that fortune eight years ago. As a little girl, I watched the money turn my family to coyotes. They were always at each other’s throats for every penny. My grandad, rest his soul, tried everything. First, he gave it to them outright, but the more he gave, the hungrier they became. Then he tried shutting it all up in the banks. They resented him for that. So, he began giving it to the poor. Well, that made them simply rabid. In the end, my cousin Lou killed him for it.”

“I’m so sorry.”

“So am I,” she sighed. “So am I.”

“If you’ll excuse the question, why did you come out this way? Why take a job in the bank? A sweet girl like you could work anywhere she like or not at all for that matter. I’m sure you could have been married a dozen times over, even save the bad eggs.”

“Because of my grandad. I hate money, but I love gold. Holding it reminds me of him, of the nights we spent in his gold mine. I can still remember how the place glistened with a thousand little suns. I even like the gold chasers, as horrid as they are to me. I like to watch them flying to the mountains to wage war with their iron weapons. In a way, they remind me of him too, I suppose. But I could never marry one.”

Samuel felt his heart drop right to the floor.

She went on. “They’re never satisfied, always wanting more and more and more. Of me and the gold, I mean. I like to live simply, see? If I marry one of them, there’s a chance they come home one day and say, ‘Honey, I hit it big.’ And I just know that after that it will be like…”

“Like your grandad.”

“Yes, like my grandad.”

He sat there, trying to absorb everything she just shared and trying not to die doing so.

“You probably think I’m mad,” she chuckled.

He swallowed the lump in his throat. “I think you’re the most wonderful thing I’ve ever met.”

As promised, he spent that night outside while Lucile lay in the warm cabin. He woke to a stiff back and the smell of bacon. He knocked on the door, and she opened it with a fresh dress and one of his old linens fashioned into an apron.

“Good morning, Samuel!” she sang like a bird.

He loved the way his name sounded on her tongue. Inside, a large plate of bacon and eggs waited for him on the table. Together, they shared stories. He told her of the many daring adventures he had experienced in the mountains while searching for gold, and in return, she nearly broke his ribs with the crafty accounts of how she left the men chasing her with their tails in their mouths.

“Well,” she said, “I better be going. I think it’s Deriville for me next.”

He knew this moment had to come, but he had done nothing to prepare for it. “I understand. Can I walk you to town?”

“That would be nice.”

So engrossed were they in each other’s company, that they had walked all the way through town and into the next before Lucile finally said, “I think we better part here, Samuel, or we’ll walk ourselves right to the Pacific.”

“Would that be so bad?” he asked.

“I don’t know. How well can you swim?”

“Better than I can walk without your hand on my arm.”

Well, if you don’t start back now, the young men will have picked the mountain clean by the time you’ve laced your boots.”

“Let them.”

She stared at him admiringly.

He handed her back her bundle, and she kissed his cheek. “Thank you, Samuel. I hope we meet again.”

“I hope so too.”

She turned to walk away as he watched on. After a few paces, she turned back.

“Before I leave, I have to know. I’m sorry for asking, but why don’t you have a mirror in your cabin?”

“A mirror?”

“Yes, in your bathroom. I see that there’s a place for one. Did it break?”

“Yes, it broke,” he said, remembering the night he put his fist through it.

“Why haven’t you replaced it?”

He couldn’t bring himself to lie to her. But, he couldn’t tell her the truth either. Finally, he answered, “I’ll tell you next time we meet.”

“What? That could be never! I can’t wait that long.”

“Then you better pray the good Lord works a wonder,” he laughed.

She gave him a little scowl before turning on her heel and heading into the distance.

When she passed out of sight, Samuel felt more empty than he had at his wife’s funeral, and he hated himself for it. He didn’t bother going out for gold that day. He sat at his dining table all evening, staring at the place where she sat, soaking up her lingering presence while it was still fresh. He didn’t have an appetite for dinner, but he said grace nonetheless.

It was difficult business going to sleep that night. He tossed and turned and never quite remembered passing into unconsciousness.

He was woken abruptly by a loud baning at his door. He sprang from his bed, lit a candle, and grabbed his pickaxe. This wasn’t the first time one of the young bucks from town had too much to drink and wanted to test their luck at robbing an old man.

With a breathing chest, he readied the axe over his head and swung open the door. There at his doorstep was Lucile in the same dress with arms folded tightly across her chest.

“Why don’t you have a mirror?” she shouted.

“What!?” he roared, not quite knowing where to put the violent energy he had mustered for that moment.

“Why don’t you have a mirror,” she repeated all in a fit, apparently unphased by the axe still hanging over her head.

He looked down on the dainty woman, fondness quickly working its way in beside the aggression. Even in the dark, he could see her cheeks roaring with the fire of life. “You came all the way back to ask me about a silly mirror?!” He let the axe fall to his side.

“It’s not silly at all. In fact, I think it is very serious, and I want to know why,” she demanded.

“Why do you want to know why?” he asked, not knowing why he was shouting back.

“I answered your question about my grandad, didn’t I? Are you going to tell me or aren’t you?”

“Come inside, it’s cold out there,” he said sternly.

“No. I won’t move a muscle until you tell me why.”

He wasn’t used to this stubbornness in Lucine, or any woman for that matter. “If I tell you, will you come inside?”

“Yes.”

He signed. “Okay then.” He propped the axe by the door and tried to relaxed himself. Still, his nerves were firing with dizzying rapidity. He shut the door behind them. “I don’t have a mirror—I don’t have a mirror because I can’t look at myself.”

Lucile stared up at him through the darkness.

“I was married to a woman. Her name was Agnes. We were married for twelve years.” He felt his voice sharpen with anger. “I thought we would grow old together. She promised we would grow old together. And now she’s dead. She’s dead, and I’m dying too. Alone.”

He couldn’t stop himself from raising his voice. “So, why don’t I have a mirror? Maybe I don’t want to look at myself. Maybe I hate to look at myself. Maybe when I see one more wrinkle or one more gray hair I wish to God that he would kill me faster. Maybe every time I look in the mirror, I see Agnes. And her cancer. And my cancer. And maybe that’s just not worth having a mirror in the house for beautiful woman to brush their hair in one day and leave the next.”

Panting, he looked down again. Lucile was looking at him too. Her arms had fallen to her sides, and she was crying. She stepped forward and kissed him on the lips. He felt the warm tears on her cold face as he kissed her back.

The next thing he knew, it was morning. The sun was falling through the window directly on Lucile’s face. As he watched her sleep, all he could think was that he could not rightly keep her there without a ring.

She made them both breakfast, after which he left for the mountains, just like any other day. Except that it wasn’t like any other day. This day, he had a new fire inside him. With a full heart, he set finding gold, not for himself but for her.

As fate would have it, he found some under a stone bed surrounded by a plot of flowering pasture. Taking a fist sized chunk, he stowed it in his pocket, marked the spot, and headed to town. There, he met with a jeweler who said it could be done by that time next week.

“You can keep whatever you don’t use if it’s done today.”

The man laughed, “You must really love her, eh?”

“Love’s not a big enough word.”

“Come back at 6.”

All the way home, Samuel stroked the glistening ring in the light of the dying sun. As he walked, he spoke either one long prayer or a thousand small ones over it. He didn’t know which, but he knew Lucile would. She had been perched by the window all day and came running out before he even saw the house. Hearing her hurried footsteps, he fumbled to put the ring in his pocket and dropped it. Panicking, he threw himself on the ground to pick it up. Two tiny feet entered the frame just as he watched his hand grasp hold of it.

“What is that?” she asked, but her trembling voice gave her up.

Still on his one knee, he looked up at her. He saw not love but fear in her eyes.

“Lucile,” he began.

“Are you going to ask me to marry you?”

“I’m—”

“I can’t marry you. I can’t.” The words were spilling out faster than she could speak, “I wish I could, but I can’t. I told you I could never marry a gold chaser. I told you—”

“Lucile.” His deep voice grabbed her firmly by the shoulder. “I know you’re afraid. Hell, I’m afraid too. You don’t know if you could ever marry. Well, I don’t know if I could again either. I don’t even know how many years I could give you. But I’ll be damned if I don’t find out.”

She looked down on him, shaking slightly but saying nothing.

“Now. What I’m about to ask you, I’m only going to ask once. Got it?”

With tears in her eyes, she nodded.

“Lucile… will you marry me?”

“Yes,” she said. At last, that one little word broke her. Sobbing, she fell into his broad arms. He lifted her up and pressed his lips firmly against hers.

When they broke away, she was crying and laughing and shaking all at once. “You know what this means, don’t you?”

“What?”

“You’re going to have to finally buy a mirror.”

“Oh yeah? And why’s that?”

“Well, a woman needs some way of fixing her imperfections.”

“I don’t think they make mirrors that small.”

She laughed and hugged him tight. “Let’s go inside. I have dinner waiting.”

“Yes, Dear.”

It was a month later that the two were wed and a month after that that he started building a proper house for them. He built it in the very same pasture that he found her ring. It wasn’t much, but she preferred it that way. She also preferred to keep her job at the bank where she could enjoy the remembrances of her grandad. Best of all, the young men ceased to be a problem for her. As it happened, the rings she ran away from for all those years was the very thing that sent them running now.

Samuel and Lucile never stopped falling in love with each other. The two of them talked late into the night, read books together, took long walks, shared secrets, made love, lived life. Each day started the same. Rising early, he started a fire while she made breakfast. Shoulder to shoulder, they would watch the sun come up and the forest come alive as they filled their bellies. After a cup of coffee and a page of Scripture, they kissed and went their separate ways, one to the bank and the other to the mountains. Or so she believed.

Most days he would come home with nothing. That was just part of the job. But, without fail, he would find something by the end of the week. It was never much; a gram here, an ounce there. And it was never from the same place; this one from the river, the other from a cave. But the Lord always provided enough to keep them afloat.

As time drew on, Samuel grew sicker. It started with stomach pangs, the same as Agnes. Then came the fainting spells and the fevers. He was forced to stay close to home, and Lucile, despite Samuel’s protests, shortened her hours at the bank. But even on his worst weeks, Samuel always placed a little bit of gold in Lucile’s hand, just as her grandad once did.

One Sunday, Samuel woke up aware that he would never do so again. He knew this not from his body telling him so but by how he spent the morning. He built the fire just a little bit bigger to keep his wife just a little bit warmer. At breakfast, he couldn’t take his eyes off his lovely Lucile, her still rosy cheeks and those big eyes. He felt a special kinship with the moon who, half alive, watched with them as the sun rose to take its place among the flaming clouds. The Scripture reading was out of Ephesians five, and for weakness or for pain, he had to ask her to read verse twenty-five, “Husbands, love your wives, as Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her.” Even the coffee, far from stirring him up, settled him in his seat as Lucile rested her head on his chest.

He secretly wished she didn’t have to leave for work, but he let her go anyway. Something so beautiful shouldn’t be bothered with the ugly business of dying, he told himself. Besides, she would worry. It was better this way. All he asked was for an extra kiss, a kiss that she would forget as soon as she was out the door but one he would savor for all of eternity.

He didn’t want to leave. Not that he was afraid. He simply wished he could do more for her, give more of himself. But there was nothing left to give, no strength left in his bones. Only enough for one last thing, to take out a pencil and write this poem.

My darling Lucile,

Love enough to cancer heal

Is hidden deep inside your zeal,

There I find my hope surreal.

Hid where I least expected

Behind wrinkled eyes dejected

The mirror has thus reflected

Woman in all ways perfected.

For gold I lifelong sought.

None ever did I spot

But the darling I have caught,

Lucile with whom I’m knot.

She found it taped to the mirror when she got home. Smiling, she read every word twice over. She never knew her husband was a poet and yearned to kiss him for this surprise. Poem in hand, she scampered to the bedroom.

The paper fell as she darkened the doorway. There, motionless on their marriage bed, lay Samuel in his wedding suit. She ran to his side. Unable or unwilling to accept what was, she grabbed his hand and tried to shake him back to life. Something shiny flew from his hand to the floor. With blurry eyes, she stooped to collect it. It was a lump of gold. Even in his death, he never missed a week.

She kissed him on the lips and cried into his chest until she passed into unconsciousness. When she woke, it was black outside. She didn’t know what to do. There was nothing to do. But she wanted to see her husband again. Groping for a match, she struck it and lit the candle on the nightstand by the door. The light illumined the poem on the floor. She took it back to the bed and with a sore throat read it to its author.

She noticed something that she hadn’t before. The first word of every line was slightly darkened, as if he had traced over it two or three times. At last, she saw the hidden message: “My Love Is There, Hidden Behind The Woman, For None But Lucile.”

Immediately, she thought of the large painting that hung in their basement, that of a woman alone on a mountain prairie staring off into the sunset. Samuel had painted it himself, the only thing he had ever painted. She remembered scolding him for putting such a work of art in the basement where none would see it.

With haste, she took the candle in one hand and the poem in the other and made her way to the basement. There it was, just as he had left it. Stopping on the stairs, she questioned herself. Were these the mad graspings of a grieving widow? But knowing Samuel and his endless secrets, she approached the painting. Carefully, as though it held Samuel himself, she took it from the wall.

A large cave opened up before her eyes. But it wasn’t a cave, not exactly. It was a mine. With caution, she stepped inside. As she did, nearly every inch of the vast mine sparkled and glistened with a golden radiance. For a moment, she thought she was still asleep, lost in a dream where she was a little girl again, exploring in her grandad’s goldmine. She shook her head in disbelief. No, this was not her grandad’s goldmine. It couldn’t be. If possible, it was even bigger. What’s more, its riches would never be seen by the public eye.

One spot in particular drew her attention. It was a place where the wall recessed slightly, yet the candle light shone from there more brightly than anywhere else. Coming closer, she saw that it was a solid slab of gold about a foot tall and a foot wide, polished to perfection. She saw her own reflection staring back at her and, on the earthen mantle beneath it, a golden brush.

Dedication:

To my wife who is worth far more than her weight in gold.

Leave a Reply